16 April 2015

Researchers from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research have used the Australian Synchrotron to reveal important new detail of the structure of a drug currently in advanced clinical trials to combat Alzheimer’s disease.

Prof Michael Parker and his research team have revealed how the drug, Solanezumab, interacts with brain proteins associated with the development of Alzheimer’s; the findings highlight what makes current therapies for the disease effective, and show how these therapies can be improved.

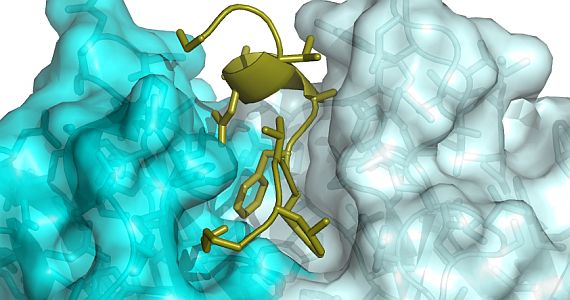

Prof Parker’s team used the high-intensity X-ray beams from the Macromolecular Crystallography (MX) beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron to visualise the structure at a resolution powerful enough to see how Solanezumab, an antibody, interacts with a toxic peptide thought by many to cause the disease.

‘This research shows us how the drug interacts with a peptide that forms plaques in the brain, symptomatic of Alzheimer’s; these peptides are otherwise difficult for the body’s immune system to clear,’ Prof Parker says.

Solanezumab works by identifying foreign molecules and ‘escorting’ them to other parts of the immune system that destroy them.

Prof Parker says the research shows the drug seems to behave in a fashion similar to a second Alzheimer’s drug, Crenezumab, also in clinical trials.

‘Our current study explains how both drugs recognise the toxic peptide and, in doing so, lays the foundation for how we can improve these therapies.’

Prof Parker says this level of understanding is essential and is informing the development of a second generation of drugs.

‘Based on this new information, and with the success of our current clinical trials, we are already developing a second generation antibody.’

Dr Tom Caradoc-Davies, Principal Scientist on the MX beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron, says the two MX beamlines are essential tools for drug development and are used by hundreds of researchers every year.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting 34 million sufferers worldwide. It is expected to become three times as common in the next 40 years as life expectancy increases. There is no cure for the disease, which damages the brain and affects memory, thinking and behaviour. Out of every ten people with dementia, as many as seven have Alzheimer’s.

The research was published today (16 June 2015) in Scientific Reports.